Peter Hoper sat alone one evening at his desk, in his small superintendent's apartment in his New York City apartment-building, a week before Christmas. He was 38 years old.

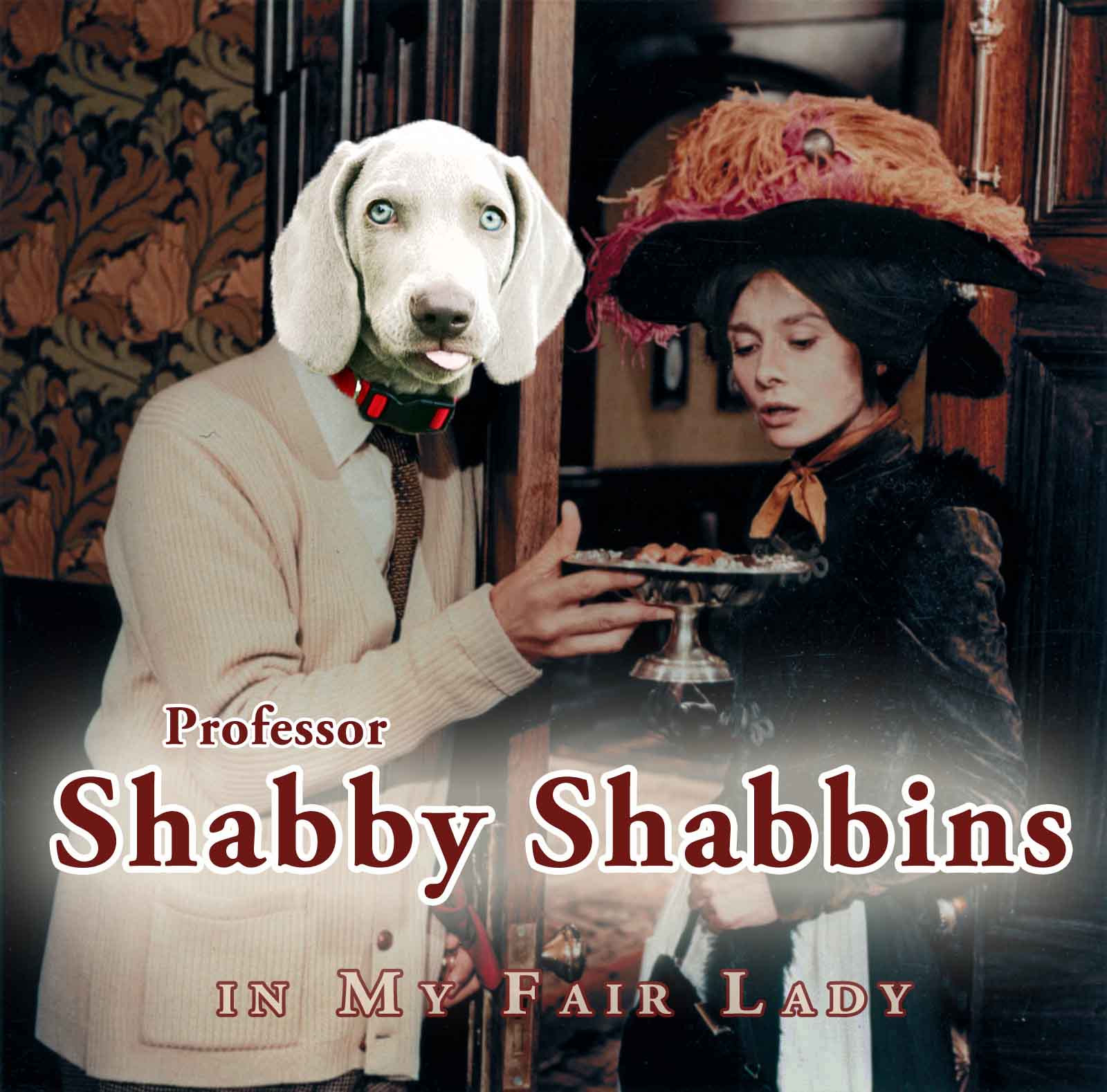

"What a waste of numbers," Peter said to Shabby, his dog. "Why have them, if they never do what you tell them to, if they just sit there on the paper like they own it? Who made them up, William Shabner? Who decided they could run everything? Numbers should mind their own business, and only visit your bank-papers when they are big and round and sweet like grapes. I never voted for the numbers, and I won't have them!"

Peter laughed and crumpled up the bank-statement on his desk. He threw the paper across the room toward the corner, where it bounced off the walls and rolled around the rim of the waste-basket until it paused - spinning softly on the rim like a planet - before it fell out onto the floor.

"So close!" Peter said.

Peter had once been a basketball player - a very good basketball player, in fact - and, as a sophomore in college, he had carried his team all the way to the Final Four. The NBA had called. And a popular sports drink had put Peter on posters all around the city. But in the last quarter of the championship, his last shot went rolling around the rim - until the ball was spinning softly on the rim like a planet - and then it fell out. And, when Peter turned around, an angry fan threw a water-bottle onto the court, where Peter slipped and cracked his knee and limped out of basketball forever.

"Take us home, Shabbicus," said Peter. "You got this."

Shabby got up from the little throw-pillow on the floor where he slept. Shabby limped across the room - he, too, had suffered a busted knee, which was probably why Peter had taken such pity on him and brought him in from the streets when he was only a gaunt homeless puppy five years ago - and Shabby picked up the crumpled bank-statement in his mouth. He dropped it into the waste-basket.

"Where were you in the championship?" asked Peter.

Shabby came over and lay down on Peter's feet to keep them warm.

Unfortunately, throwing a bank-statement into a trash-can did not actually make the debt disappear, and Peter knew it. He knew it so well, in fact, that even New York City at Christmas, with its bright lights and its snow and its happy people dressed up in their Friday-night clothes, with their good-will shining out like a miracle from their usual rusty impatience - even all this could not make him look up from the bills on his desk now. He was mentally struggling against the numbers, when he heard a knock on his door. Or rather, he was aware of a knock on his door like someone in a dream. He ignored it. And he may never have noticed it at all, if Shabby had not finally stood up under the table and made a noise that was not a bark but more like a laugh (if dogs can laugh).

"Is someone there?" asked Peter.

The big oaken door was silent, now, and its metal plate with the apartment-number was not rattling like it would if someone had knocked.

"Just the wood creaking, Shabbiah LeRuff," said Peter, "or maybe we're both getting too lonely being cooped up - "

Someone knocked on the door - this time there could be no mistake - and the metal plate was tittering on its rusty loose screws with a sound like a stifled chuckle, like the sound a mouse might make if it were trying not to laugh, Peter thought. The door rapped again and Shabby trotted forward between Peter and the door. Shabby looked back and forth with his soft eyes glowing like he was waiting for something to happen - something to match the Christmas goodness that was taking place outside in New York City.

All right, all right, Shabmartigan," said Peter, and then louder, "Yes, I'm coming. Just a minute."

Peter got up from the wooden chair, and he made the few paces to the door, where he looked out through the peep-hole. But there was only the wall across the hall.

"Hello?" he asked.

And then, where there had been only a view of the wall, there came a wave of rippling light, soft and pleasing as sunshine on water, with elegant fingers dancing through the glimmer - a beautiful young woman was pulling her hair back behind her ears. She had just stood up from the shadow at the foot of the door. The light of the fluorescent bulbs in the hallway seemed to hover upon her. She leaned close to the door and whispered like she had a secret.

"I'm sorry," she said. "I was tying my shoes. I'm not very good at it yet."

"I won't tell anyone," Peter whispered.

He opened the door, and the young woman stood there in the hallway. She wore jeans and a sweater and little white pumps on her feet that were tied in perfectly symmetrical bows.

"Can I help you?" he asked her.

"I was hoping I could stay here."

"Ah, it's a bit late for that," said Peter, "but we have a room on the second floor, if you want to take a look at it. First and last month's rent have to be deposited up front. And then the monthly is $500, which is the lowest price around. But dess iss special price yuss for speshall agent, Shabble-0-7."

Peter laughed. He had turned around, and he was scruffing Shabby about the head as he picked up the stick with the metal keys off his desk. But when he turned back, the young lady was right behind him - inside his little superintendent's apartment - and she was looking around. She was pulling her hair back behind her ears again, with her hands now covered up in the sleeves of her sweater, so that only her fingertips ran through her shining hair. There was a warmth in her soft sky-filled eyes. And Peter realized that she was fully possessed of that wholesome naivete - that sweet belief that faith and beauty and good-fortune were all the same thing - which drew so many young women to New York City, and which left them hungry and abandoned like a warning before it turned them into something worse. And Peter also realized that she would have no money.

"Oh," he said.

With her palms over her heart, the young woman was looking at a bright painting that Peter had on his wall.

"Actually," said Peter, "I just remembered that a new family was moving into that room today. It was the last one we had open."

"That isn't true, Peter. Do you really not want me here?"

She turned to him and winced, and Peter dropped back into the chair at his table, as if she had struck him. He felt his breath go out of him. She had hurt him by her honesty, by the way that she had looked at him, so troubled and so fragile (as we all are), now sharp inside him like a blade that had gone in and come out too swiftly for the blood to even be flowing yet. And he put his hand to his chest. For you were supposed to stop asking people Do you like me? (which was what the young lady had meant) by the time you grew up, and it didn't matter that the question was still there - it would always be there inside you, trembling like a dew-drop (as it is for everyone) while the world seemed to march by so confidently; but still you had to stop asking that question, because it required enormous strength, the strength to keep getting stepped on and crushed over and over. Only children were that strong. But the young woman had asked him, and she meant it.

"Please, Peter," she said. "Let me stay here for Christmas with you. I'll do anything you want."

He looked at her. He stood up and took her forcefully by the arm.

"This isn't that kind of place," he said.

"I don't mind, Peter. I can do anything - I'll do anything really."

"All our rooms are full," he said.

"Please, Peter. I'll make you a train, or an airplane on a string, Peter. I'll make you that basketball-card you wanted - the one you traded that kid for, only he cheated you because he was leaving school and he didn't tell you, remember?"

"What?"

Peter stopped and drew a sharp breath.

"How did you know about that?" Peter asked. "Is this some kind of joke?"

"No, Peter. I want to spend Christmas with you."

Peter looked at the clock - it was already 11pm - and he was still holding the stick with the keys in one hand. He pushed the girl out through his door. Then he marched her down the hall, up the stairs to the open apartment on the second floor.

"There's water and heat," he said, "and there's a chair and a bed and a desk. You can stay until 11am tomorrow. That's one night. And when I come for you in the morning, you leave."

He stepped backwards and closed the door before she could say anything. And then he was in the hallway, alone, asking himself why his hands were shaking and how she knew his name.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

Peter passed an unpleasant night. He was at heart a gentle person, or so he believed himself, and he tossed and turned on his mattress with the tingle still in his palms of how he had shoved and gripped that poor girl and slammed the door on her in the vacant room. Maybe even now she was at that room's desk with her fingers in her hair. Maybe even now she was wondering what to do, where to go, whom to ask for help, just as Peter had been crumpled up over his bills earlier - only her suffering would be worse, Peter realized, because she was a woman, and women were more envied and more hated and more cast upon with people's dark hopes of degradation. Peter's grandmother had told him. Peter's grandmother had been a rock and sky of a woman, but she had told him that she was a precipice, too, and that she had to lose herself or keep herself by the choosing every morning. He didn't want to hurt the poor girl on the second floor. But the way he had gripped her and shoved her, especially after what she had said - what had she said? - Peter turned over again on his mattress.

The gray light of a New York morning in December was seeping through the window on the other side of his apartment, taking hold of his room in that oblique, hurried, selfish but not unkind way that characterized everything in New York City, from its great business sectors to its angry homeless. And at last Peter got up and stepped into his shoes by the door. Shabby was watching him.

"I got a feeling, Rufeus Shabrid," said Peter, "that today is going to be lousy."

He opened the door, and he and Shabby both limped out - Peter in his sweatpants and jacket and winter work-boots, and Shabby hobbling quietly ahead. They went out on the stoop of the building in the cold while the sky scratched itself with the gray and gold of dawn. It was too early for anyone to be passing this way, or if they did pass, it was too early for them to care what Peter looked like or how Shabby relieved himself like a female because it was freezing and his leg was hurt anyways. Peter picked up the newspaper. On the front page, the US senators had voted unanimously (all but one senator from the great state of Hawaii) to bail out a large bank and its shareholders from their debts.

"Must be nice," said Peter to Shabby. "Come on, let's get you back to your castle."

Peter went out and performed the necessary scooping up in a plastic bag, which he dropped in a dumpster out to the side of the door. Then, after a shower and a change of clothes, he spent the morning looking through classifieds for part-time work. He amused himself by writing up a personal ad.

Busted leg but still in prime health. Good-looking. Friendly. Would like to meet an attractive adventurous partner. No tramps. Must have proper human owner. The Lord of Downtown Shabbey.

It was Sunday, a week before Christmas morning, and Peter knew before he even went out into the hallway that he lacked the heart to turn the poor girl on the second floor out into the streets on a Sunday. He lacked the heart, in general, to be rough with people, most likely because he had been born tall and athletic and healthy but also absurdly fragile inside and he thought that everyone else was just the same. Except for his grandmother, maybe - she was tough without being mean. But everyone else he suspected of being much softer than they looked. And more than half the people in the building had grown wise to him and were late on their rent (which it was Peter's responsibility to collect) because they saw how incapable he was of asking for it.

For example, the Larosa sisters, who always answered the door wearing matching gold crosses that they had received for their shared quinceañera - while one went for the rent the other would step back so Peter could notice their second-hand furniture and the smell of eggs and lentils they were eating again to save money for the local college. Then Peter would make up something about student discounts, or a holiday bonus, or a government gift-back, or anything. He would turn and escape before they brought him the crisp hundred-dollar bills that they saved in the dresser in their shared bedroom. And there was old Mr Rocker, too, who always answered the door with his keys in his hand, because he worked three different driving jobs to pay off medical bills. And there was old Mrs Laughley, who never answered the door at all. Instead, she sent her grandson, Little Jim, who reminded everyone of Peter and who was widely regarded as a prodigy at the piano academy he loved, to invite Peter to his next performance, which also meant that his grandmother was still using all her pension to get him lessons. They were all so earnest, so relatable. They were mercilessly human. And Peter had never stood a chance with them.

He doubted he would have any more of a chance with the young woman in the vacant room.

"Hello?" he knocked on the door. "Miss? It's Peter, and it's 11am."

"Of course it is!"

She threw the door open, smiling, with the inrush of air moving in her hair again like the sun rolling out of the clouds onto a wheatfield. She took him by the arm, and Shabby ran in making that noise he had made the night before (more like a laugh than a bark). The young woman pulled Peter inside, where Peter smelled fire - except it wasn't fire exactly, not something burning like that. No, it was a fire with a sweet, delicious, Christmas-like smell that made Peter want to lie down wherever he could find a soft place and just be nothing but contented.

"Hi, Peter."

Little Jim Laughley - the piano prodigy - must have had the same idea. He was sitting there in the room, snug and low on a bean-bag chair, with his feet out and his shoes off and a plate of pancakes on his lap. He was smiling at Peter while he cut himself a bite of pancake that was drenched with golden syrup. Then he paused to drink from the hot mug beside him, which rested on a cardboard box that had been flipped upside down to make it a table.

"Feels nice in here, right?" Little Jim asked Peter.

"Why does it smell like there's a fireplace?" asked Peter. "What is that?"

The young woman had somehow stepped adroitly onto Peter's heels and pushed him out of his boots, so that he was now in the middle of the room in his socks on the carpet. The place did not feel lonely or empty at all. It felt full of promise - the bare wooden walls and open spaces were seemingly brighter, as if with the shining hopes of someone who had at last found a place to make a home, someone just moving in, moving up, starting over and better - and Peter groaned at what that meant. The young woman pushed Peter down into the chair across from Little Jim Laughley. She stepped back, beaming.

"It's her magic that makes it feel and smell like that," said Little Jim. "She's an elf."

"An elf-let," said the young lady. "I won't be a real elf until I make a Christmas miracle."

"Of course," Peter said. "Of course. I forgot. We can't have an elf without a Christmas miracle."

He winked at Little Jim, who laughed, but the young woman only snapped her fingers and went whisking off between them toward the kitchen. She sang a Christmas carol that made Shabby follow along behind her, howling a low, grumbly noise of pleasure while he wagged his tail. He followed her around the counter, where she opened up the cabinets and pulled down a great big box all wrapped up with Christmas paper and a bow. And she balanced this box atop her head while she walked back into the room, with one hand holding a plate of hot pancakes, and the other holding a hot cup of coffee.

"It's your Christmas present, Peter," she said. "I think it's gonna be good."

Peter took the pancakes and coffee from her, and she set down the box over in the corner.

"You're such a good boy," she sang to the wall. "And I wouldn't forget you."

"What?" Peter asked.

"I wouldn't forget you! Oh no, oh no! Did you think I would forget you? Did you? Who's a good a boy? Who's a best good baby boy? Shabbra-cadabra!"

She spun around and - Peter had no idea how she had carried it - there were crisp carrots in peanut-butter in a bowl in her hands, which she lowered to Shabby. She sang a Christmas verse over his shoulders while he yipped into the bowl, eating. And then she sat back on the carpet, sighing, leaning back on her palms with her thin arms bending slightly over-straight at the elbows, and she smiled at Peter. She was still in her jeans and shirt from the night before, with her toes wiggling in candy-striped socks.

"Gave up on the shoe-laces?" asked Peter.

"Elf-lets don't tie their shoes," she told him. "Santa makes us all a new pair of boots each year, and each pair is special, with big soft wool fur that fits perfectly to our feet and keeps our little toes warm while we yearn for Christmas miracles."

"I thought you made toys."

She shook her head.

"We let the markets take over years ago," she said. "I mean, we still can make a fine toy - I mean craftsmanship and not just flash. And it's always nice to make a toy because it's simple. But now we have more time for the hard stuff. The holiness and the hope and the miracles. You know, the way that people just start feeling better and their good-will shines out from them no matter how rusty they feel, and there's more laughter - people forget that laughter is a miracle - and we - "

The door rapped.

"It's my Granny," whispered Little Jim. "She's gonna make me go to church."

He set his plate on the cardboard box, with the metal fork scraping just enough to make him wince, before he stood up silently and crept to the fire escape at the window. He climbed up like a cat and disappeared. The door rapped again. Peter put his finger to his lips to signal the young woman in the candy-striped socks to be quiet. But then, out in the hallway, old Mrs Laughley began singing. She was singing her Sunday church-songs, in her long sonorous voice, with her rhythmic breathing, with the keys in her purse jangling because her whole body would be shaking in her Sunday dress as she reached deep for the notes and made the air wimple with sound - and then Shabby suddenly howled out long and sad and hopeful with her. He howled again and barked.

"Just what I thought," said old Mrs Laughley in the hallway.

"Way to go, yond Shabbius," whispered Peter, "now get to the pulpits and cry liberty, why don't you?"

Shabby whined and hung his head, hiding behind the big box wrapped in Christmas paper, while Peter went to the door.

"Mrs Laughley!" Peter opened the door to her. "I'm so glad you're here! How's the new sealant on the windows holding up?"

"Where's my grandson, Peter? It's time for church!"

"You... have a grandson? Are you sure? I've never seen a grandson here before. What's a grandson? I've got a Shabby - as a matter of fact, I've got a Shabby to spare, although he's not particularly quiet when you need him to be, if you understand what I mean."

He glanced across the room, and Shabby whined again and lowered his body with his head on the carpet. He came snuffling out slowly, circularly, to the candy-striped socks of the young woman, where he snuggled up against her feet while old Mrs Laughley came inside. Mrs Laughley used her umbrella to poke the bean-bag chair, which belonged in her living room. She glanced at the window and looked up the fire escape, and she even crouched down, with her nimble old body like a curious bear, while she smelled the pancakes on the cardboard box, until at last she noticed the young lady with Shabby. Mrs Laughley's eyes brightened, and she straightened up.

"Peter!" she said, opening her arms. "You have company! Who is this young lady?"

"She's an elf."

"An elf-let," the young lady said.

"Wonderful!" said old Mrs Laughley. "Of course she is."

She turned and drew Peter closer to her by the counter, where she unfolded a Christmas catalogue and spoke in a low voice.

"Look here, Peter," she said quietly. "I had to scare off Little Jim with church this morning so I could talk to you. This is a digital piano with dynamic expression so that it looks and feels and sounds and plays just like a real piano, except that you can use it with headphones, so Little Jim can play all he wants at home, too, and without bothering the neighbors. And it's crazy expensive, so I told him no. But then look here it's on sale! It's half-off for Christmas! And what a surprise it would be for him! But the thing is... if - "

Peter cut her off, and he could already feel himself shuffling backwards, stooping a little, trying to get down to her height, as if in apology.

"You know, I've been meaning to talk to you," he said quickly. "The management's doing a Christmas thing this year, where they pull a name out of a hat for one person to have December's rent waived, so long as they use the money on something Truly Christmassy, or that's what they said. And this sounds exactly like that. So, I'll just make sure it's your name that's pulled, and you let me come up and listen to Little Jim play while you sing for me, or maybe both of you can sing for me, or maybe I'll even sing for me. And we'll all be singing. So don't worry about it. Just get along to church with you so prettied up."

"Bless you, Peter!"

She seemed to throw herself at him, hugging him tight, almost like a child was hugging him through an old woman's body, with all the years going away from her while he patted her softly. Then she turned and went bustling out of the room, wiping her eyes. But no sooner was she gone than someone was knocking on the door again.

"Mr Hoper?" the Larosa sisters pushed the door softly open. "Mr Hoper, can we talk to you for a minute. It's okay?"

"Of course," he said. "Come in. I'd offer you a seat but - "

"No, no, it is good like this," said one of them (they were twins and Peter could never remember which was which). "We are coming for... you see, our father is getting the Christmas time with no work - No work! I mean, he is not having to work, and it is ten years..."

Peter waved his arm to stop them.

"You know, I've been meaning to talk to you girls about something," he said.

He straightened out his jeans and flannel-shirt as if he were a man too well-fed and well-pleased with himself to ever have to lie. And he told them exactly what he had told Mrs Laughley, except this time the management was pulling a name off a Christmas tree at one of their swanky hotel parties. Peter was invited, and he would make sure to pull their names, so long as they spent their money on getting their father up to see them for Christmas - and if they let Peter come by and eat some tamales with them. And they hugged him and kissed him on the cheek. But when they left, old Mr Rocker was there with a worried look on his face, and by the time that he and Peter had finished talking, the building-management's party included the mayor, the police commissioner, one senator, and even the Parrot-Head Guy who walked around everywhere in New York City with a parrot on his head, and Peter had been asked to pull out of a sculpted Christmas stocking the name of a lucky tenant, who, of course, would be Mr Rocker. The door closed and Peter sank down against the wall.

He was half crumpled with his knees up and his face in his hands, and Shabby was somehow lying down on his feet again, aware of him, with that instinctual kindness and tact of a good dog. And Peter breathed and pressed his palms into his eyes for a long moment. But when he finally looked up again, he saw the young woman still across the room. He jerked up to his feet. He laughed too loudly and straightened out his clothes.

"Ha!" he said to her. "The management's going to give me hell for this! But I'll work it all out."

"Don't be ridiculous, Peter," she said. "There's no management."

Peter had tried to pick up his coffee casually, but now he couldn't drink it because his hand was shaking - the young woman was staring at him.

"You bought this whole building," said the young woman, "all those years ago, with the money from your drink sponsorship. Because you knew your grandmother wouldn't leave it. And that's why you're in so much trouble now."

Peter stood still for a long moment. Then he banged the mug down (burning his fingers) and he turned and walked out and slammed the door as hard as he could. And then, a minute later, he opened the door a foot and Shabby ran out, and Peter tried to slam the door again but it didn't sound as good.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

"How does she know these things about me?" Peter was talking to Shabby while they walked around the neighborhood that evening. "What right does she have? Do you think Mr Stacks sent her here? Like a spy or something, to feel out my weaknesses? I bet he would do something like that."

Shabby growled at the mention of Mr Stacks, who was the head of a Wall Street investment group. Mr Stacks had once offered to buy Peter's building and put him out of debt. But then Mr Stacks would surely raze the building and slap up a new high-rise and charge five times the rent, and everyone who lived there now would be just thrown out, too bad, that's life, that's New York City. Well, it wasn't New York City for Peter, and he said no. He had said no the first time five years ago. That was the very same day he found Shabby, as a matter of fact - after Mr Stacks had left, a car's engine had roared to life outside, followed by a thump and a wounded cry from a puppy. Peter had gone out to check and found Shabby at the curb, whimpering in pain with a freshly-broken leg.

"That heartless wolf," said Peter. "He probably sent her to spy on me. You know he's offering to buy again. Three times as much as last time! We could get you a lady friend and dress her up in pearls with that much money! We could call her Shabril Lavigne! Why, with that much money, we could pay off all our debt, and you and me and Shabbiah Twain could have ice-cream and peanut-butter carrots and every sports-channel for ever and ever, amen."

Shabby barked as loud as he could.

"I didn't say I was going to take it!" Peter told him.

They walked back inside together, and instead of taking the rickety elevator, they trudged up the creaky stairwell to the third floor. They went to room 316, where Peter rapped softly and then pushed the door open to old Mrs Laughley's apartment. She was seated on her couch with old Mrs Garthry and Mr and Mrs White, who had all been friends of Peter's grandmother before she passed away. The Larosa sisters were sitting on the floor with the young woman who had called herself an elf-let (she was wearing different colored candy-striped socks now). And several more people were gathered around a cake at the table, where a half-dozen children were sitting and bumping around in place with paper plates and plastic forks. The children had icing-dappled smiles on their faces, and one of them was taking a picture on a phone.

Then everything seemed to pause. Everyone looked at Peter. Little Jim raised up his arms and put out both his hands with his fingers spread, and he jabbed them into the air and pretended to play a piano, but he was making the music with his mouth. Then old Mrs Laughley and Mrs Garthry burst in singing. Then the Larosa sisters started clapping, and everyone, too, was clapping and singing now - and so they gathered, coming together in the living room, all sitting down on the carpet or the sofa or the chairs or leaning against each other, until the song was over. Peter was smiling, and Shabby was going around, nuzzling everyone like a chain-letter of touch and affection between them all.

"I guess we better start with good news," said Peter. "We have a new guest. She has gone through a rigorous selection process, conducted by the Three Wise Men - myself and Little Jim and our ordained Chief Shabbi - "

"Blasphemy!" whispered Mr White.

"And we have decided that she makes delicious pancakes. And she also makes delicious carrots with peanut-butter. And she can stay for the holidays!"

Peter clapped and everyone else joined in, clapping and saying "Welcome!" while the young woman in the candy-striped socks blushed. She folded her hands in her lap and twisted them together, almost like a child, smiling and blushing, until she got up onto her feet as if she were feeling too happy and buoyant to stay sitting down. She bowed to them and laughed embarrassedly - that magic, trusting, innocent laugh of people who are too good in themselves to imagine anything less good in others.

"Thank you!" she said. "Thank you! You can just call me Elflet, because I am an elf-let. But I'm going to do my best to bring Peter a Christmas Miracle, and then I'll be a real elf! A real elf, can you believe it?"

"Of course!" said old Mrs Laughley kindly. "Of course you'll be a real elf!"

Everyone clapped for her again, and she sat down, still beaming. Then the Larosa sisters told everyone their father was coming, and they were going to make tamales on Christmas Eve at a small party with some space-heaters up on the roof, if that was okay with Peter, which it was. And Mr White said his grandson was now a pro-gray-mer (a pro-gamer, Mrs White corrected him) and that he was rich and famous as cats on the internet. And they clapped again and settled, and some of the little ones went sneaking off to a corner with their mothers' phones while everyone relaxed where they were sitting and looked at Peter.

"Ah, yeah," Peter scratched his head, "I didn't have a whole lot of time this week, but I'll give you what I've got. Been getting a feel for it with Shabby on our walks. But, look - "

"Come along!" burst out Mrs Laughley. "Give us a good one, Peter, and a funny one, too!"

Peter's grandmother used to host this meeting, once a week, which had started with just some of her friends in the building. But it had changed and grown, one day, when Peter's grandmother asked him to tell a story while they were waiting for Mr Rocker - and Peter's story made everyone sigh and sit up and laugh and believe at all the right times. And since then, they asked Peter for a new story whenever he came. And they listened because he told them their own story, just in a different way each time with different names, but it was always them (the very people in the room) and they were the good brave people who were pressed up against hard times, but they always held on tight to the end, until things turned out right, and light beat out darkness, and love beat out hate, and hope proved itself gold and solid through the fire, and friendship was real, and so was courage, and so was life the whole, grand, wonderful, rapture of it. And that was Peter's story tonight, too, and when he finished everyone clapped and sighed, and old Mrs Laughley said Peter's grandmother would have been proud.

"That was unbelievable, Peter!" said the young woman with the candy-striped socks.

"Yes," said a harsh voice in the corner. "That was unbelievable, Peter."

Everyone turned to two men in suits, who had come in quietly during the story. They had stayed there aloof in the shadows. One of them was smaller, with sharp eyes like a wolf, and one of them was much bigger with a broad face like a gorilla - it was Mr Stacks and his body-guard - and Peter leapt up and ushered them both outside.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

"You've no right to be here, Mr Stacks," said Peter. "Of course, you're welcome if you want to come hear a story and talk, but if that's the case there's no need for a body-guard. And you should have tried some cake. Now, why are you here?"

They were down in Peter's little superintendent's apartment. He had just finished pouring out a kettle of brown tea into three cups where they were sitting at the table - for as much as Peter hated Mr Stacks, he considered it beneath his own private dignity to let someone pass through without offering them a drink. The huge body-guard sniffed the tea and smiled when Peter pushed him a jar of cookies.

"Thank you," the body-guard said.

But Mr Stacks glanced over coldly, and the body-guard lowered his eyes to the table. Then Mr Stacks turned back to Peter.

"Oh, I'll have some cake eventually," said Mr Stacks. "In a way, yes, I'll have my cake. But I guess you might say I'm playing with my food. Because you know you're done, Peter. You're swallowed. And I'm about to gobble this place up underneath you. But why make it a hassle? Why make the bank break you apart because you can't pay the property tax? Why go penniless, profiting nothing, while you watch the bank sell me everything anyways piecemeal? Let's help each other even if we don't like each other."

"There are few people I don't like," said Peter. "And, unfortunately, Mr Stacks you've given me very little reason."

"Well, how about this? Five times what I offered you five years ago for the building. Almost twice as much as I saw you about two months ago. And I even have the contract ready. Right here. But it must be signed and posted or put in my hands before the New Year. And this is my last effort at generosity. After this, I will simply sit back and watch the world digest and excrete you into your misery."

Mr Stacks dipped his long sallow fingers into his suit jacket and removed - with a rustly, scraping, hissing sound that it seemed he was deliberately trying to prolong - a fold of papers, which he set on the table. He slid them across to Peter. Then he tinkled his little spoon in his teacup while Peter looked over the contract. It was exactly the same as the other contracts, except for the payout. Peter recognized it, from the first sad letter to the last abrupt period in its finality, and Peter's lawyer even five years ago had told him to take the deal. He had to take the deal, Peter realized. He was trapped and swallowed, like Mr Stacks had told him with his hypnotically cold voice, and here was a last way out, offered to him just in time, one last time, with the only difference being that it was five times as much as five years ago. Now, it was more than enough for him to live on richly for all his days. There was a pen beside Peter on the table, now, which Mr Stacks had just put there, and Mr Stacks was leaning back to his teacup again.

And what a fine pen, it was! Silvered and elegant and heavy on the cheap thin wood of Peter's desk. The pen was gleaming brightly in spite of the cheap dim lights above Peter's head. It was a pen of great power, and it belonged in a powerful man's hands, a man like Peter, should he take it up, should he hold it and wield it to sign his own name like a seal of his authority to have and direct the destinies of lesser peoples - what strength he had in his own name! In his own self, Peter thought, as he held the pen. He looked upon it, and over it, and then he noticed the young woman in the candy-striped socks, standing in the corner, where she must have slipped into the room unnoticed after them. And Peter felt ashamed.

He set the pen back down on the table.

"I'm going have to think about this, Mr Stacks," said Peter.

"Sign it or I'll break your arms!"

Mr Stacks banged his wrinkly fist on the table, and his teacup jumped, clinked, rattling as he waved his arm at the huge man beside him, the body-guard. The young lady in the corner of the room stepped back. She gasped and shrank against the wall. But Peter only felt the calmness of pressure, like he used to feel when he had the ball and time was running out, and he reached out for the contract, crumpling it coldly between his palms.

"You know, Mr Stacks," said Peter. "I don't even need a Shabby this time."

He threw the paper without looking, and it dropped dead with a thud into the waste-basket across the room. And then Peter stood up, walking calmly past the gorilla-like body-guard to the door, which Peter opened as he stepped back from the threshold. Peter simply stood there. But, in that moment, he was possessed of a human courage that was neither feigned nor spoken, but primal, or even spiritual, and therefore undeniable in the way that it broke both Mr Stacks and his body-guard where they sat at the table, so that they slumped like mastered animals, like children caught puffing themselves up with imagination. The body-guard blushed and hid his eyes. And even Mr Stacks shook with the force of it, before he lunged up and knocked his teacup over so that it spilled across the table. Mr Stacks started for the door.

"Don't forget your pen, Mr Stacks," said Peter.

And - still - the power of it was there, the human power, stopping Mr Stacks, so that he turned slowly, almost as if against his will, and picked up the pen. He snapped at his body-guard, and they went to the door and walked out together. But, at last, in the hallway, the spell was broken. Mr Stacks jerked to a halt. He turned around again and stepped close to Peter.

"You know, Peter," he said quietly. "To anyone watching it would have looked like an accident, just like an accident. But I saw the dog the whole time. And I did it because I wanted to, just because I wanted to, because I am a man with a car and it was a stupid dog. And because you are a ninny - I can go around and break anyone or anything I want to, and some little ninny like you will clean up after me. In truth, that's all you're good for. You know you can't fix it, you can't help, but you're lonely in your misery and you want to share your misery. That's all. But I won't let you infect me with your failures. I rule, and you squabble, and that's the way it will always be."

"Merry Christmas, Mr Stacks," said Peter coolly.

But Mr Stacks was shaking his head as if he were not yet finished. He had eased closer, speaking even more softly now, with his right hand at the buttons of his vest, playing with them. He was preening himself. He was smartening himself, strangely, as if he were adjusting not only his clothes but rather the pleasure of his own malice around himself, like some stately invisible robe he wore that only he could feel, but which made him infinitely regal and powerful in his own opinion.

"And another thing, Peter," he said. "I broke your leg."

"You give yourself too much credit, Mr Stacks. I've met the man who broke my leg."

"Ha!" he laughed. "Isn't that just how a little ninny like you would see things? I don't mean I threw the water-bottle, Peter. I mean I had a half-million dollars bet on that game, and I made sure I won."

Peter understood.

And suddenly there was a flashing bright light of rage in Peter that blinded him. He couldn't breathe - and then he was falling to the ground with the body-guard's fist still in his chest, because he had lunged at Mr Stacks to kill him. The body-guard had stepped in the way. He had punched Peter hard in the ribs, and now Peter's back hit the floor and he bounced there on the carpet with the body-guard standing over him. And Mr Stacks was just laughing, turning, walking away, as if it had been no more than a sweep of his arm through a castle of wooden blocks and now he was bored again. The body-guard pulled the door closed with a slam.

The young woman in the candy-striped socks was beside Peter, holding him gently at the shoulder, because he couldn't breathe. The wind was knocked out of him. But, at last, his breath returned, and he lay there gasping, listening to the body-guard's heavy footsteps go down the hall. Shabby howled and growled and whined and lay down by Peter there in the floor. Then Peter let himself go limp, resting, staring at the ceiling, wondering if what Mr Stacks had said was really true.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

"You own this whole building?" asked Little Jim.

Little Jim climbed in from the fire escape as Peter got up slowly from where the body-guard had knocked him down.

"What?" said Peter. "What are you talking about? I wish I owned the whole building. How long you been there?"

Peter had shuffled over to the arm-chair to sit down. He was holding one hand to the center of his chest, where he wondered if a rib was broken or if the skin would turn purple and bruise with the color of a dying mushroom. He had to lean on an elbow, hitching his breath as he sat back, until his back was against the chair and he could relax. The young woman in the candy-striped socks - Elflet, the elf-let - had gone over to the little kitchen, where there was a sound of running water and ice tinkling. But Little Jim just stayed standing there by the window with his eyes wide.

"Mr Stacks wants to buy the building?" he said. "And he wants you to sell it to him. But why doesn't he ask the managers? Do you really own the whole building, Peter?"

"No, no. I just - "

"Yes," said Elflet. "He owns the whole building."

She appeared with a glass of cold water in her hand, and Little Jim let out a long slow whistle. Little Jim ran his palm back through his hair with his eyes shining while he looked at Peter. Then he put out his hand and started counting, mumbling, tapping one set of fingers with the other while he shook his head.

"You got to be rich, Peter!" said Little Jim. "Why're you living here? You should be in some big place where they have one of those real pianos. Then you could call me up and say Hey Little Jim, come on over and play me this piano. And I'd say, Okay Peter. Man! Why're you living here?"

"He's broke," said Elflet. "And he doesn't really believe. That's why I'm here."

"He's broke?"

Little Jim fell back onto a sofa cushion across the room while Elflet handed Peter the water. Then Elflet just stood at the chair beside Peter, looking at him. Then she knelt down beside him. Then - strangely, like something from a book, because Peter was too stiff and breathless to even stop her, or to take a drink, or to get her and Little Jim to quit talking about things they had no business knowing - she kissed Peter's hand once. And Shabby came over and lay down on Peter's feet for warmth, where Shabby gave out a low, brief whine that would have sounded like sympathy to anyone but Peter. Except Peter recognized it as pride. Shabby was proud of something that had happened to Little Jim, an instinctual homage and respect that had befallen the boy, who was now looking at Shabby and Elflet and, between them, Peter, with a great gleam in his boy's eyes, as if he were saying to himself, Ah! So, this is to be a man!

Peter was troubled at the thought.

"Now, look," said Peter to Little Jim. "It's not - "

"You're too soft, Peter!" Little Jim leapt up to his feet. "That's your problem!"

He stood there and his chest swelled and his arms went back, and Elflet sank a little on the carpet, leaning against the chair, watching Little Jim while he started marching around the room.

"I bet all these people aren't paying you any money!" said Little Jim. "That's just like you! I know you want to be good and all that, but you got to get paid, too. You got to show people who's boss. I mean, look here at me. Look. I'm little. But I don't let people push me around, not even Granny. I always tell her I'm going here and I'm going there and she doesn't try to stop me because she knows there'd be trouble. She knows I'm a man. I'm a man like you, Peter - "

His face colored.

"I'm a man like you, Peter, and I let people know who's boss, even if it's - "

The door rapped loudly. Then it was pushed open - not with presumption or incivility but with the cool crisp motion of someone who has determined not just a right but a responsibility to enter a place - and there in the threshold, stooped with her glasses shining on her old face, but also holding herself up in a vigor that belonged to dignity and a monumental presence of character, stood old Mrs Laughley, Little Jim's grandmother. She stepped inside. She didn't say a word, and she didn't even look angry, but she only smiled in her great and ancient strength (which was so much more terrible for its kindness) and Little Jim's mouth dropped open. He closed it and sat down and stood up and put his hands behind his back.

"I thought I heard my grandson's beautiful voice down here," said old Mrs Laughley. "It's time for bed, Little Jim."

"Yes, Ma'am."

She stepped swiftly across the room - surprisingly swiftly! - and she was there in front of Little Jim before anyone else had moved. Her arm was raised up. But she only laid her palm softly on Little Jim's curly-haired head. She bent down and kissed him, pulling him to her side as she looked over at Peter. And a flash of pain went through her eyes when she saw Peter slumped in the chair. The bulk of her twitched as if poked with a stick. But then she straightened up again, for she was a proud woman, a proud woman with great compassion and wisdom, who knew that Peter did not want to be seen as weak, wounded, and crumpled, but rather as the good strong man he was trying to be, even if they both knew how rarely he succeeded.

"What did that evil Mr Stacks want, Peter?" she asked.

"Oh, Granny!" said Little Jim. "Did you know that - "

Shabby barked and Peter sat up, and Little Jim stopped, looking at them - his fellow Christmas Wise Men - and he understood.

"Nevermind," said Little Jim.

"Nevermind what?" asked his grandmother.

But Little Jim's eyes were suddenly going over the room, searching, as if for a change of subject.

"I mean," he finally said, "did you know that I think Elflet looks kind of like you?"

"She's too pretty," smiled old Mrs Laughley. "But thank you, Jim. And, actually, I was thinking earlier that she looks a little like my sister."

"She is looking like our mother," the Larosa sisters peeked in at the door.

"I think she looks like my wife, God rest her," Mr Rocker said as he came in around the Larosa girls.

"She looks like Aunt Alya!" shouted one of the kids, among others, who had been upstairs earlier and who all came running into the room now.

"What is this?" Peter stood up. "How many of you are out there?"

He stepped toward the kitchen, hiding the stiffness in his body, but old Mrs Laughley stayed him with a gentle touch of her hand on his elbow. She nodded at the door, and Peter looked. And, one by one, everyone who had been upstairs earlier filed into the room. Mrs White came last, holding a small package in Christmas wrapping with a bow on it, which she carried to Peter and put in his hands. She went up on her tip-toes and kissed him on the cheek and hugged him.

"Merry Christmas, Peter!" she said.

"Merry Christmas!" they all said.

But he only stood there.

"Go on!" said one of the children. "Open it, Peter! It's a - "

This boy was stopped by his older sister, who put her hand over his mouth. Then the boy's eyes widened and he tapped himself gently on the forehead, as if to say he understood, and he started dancing and wiggling until his sister let him go again.

"This is... thank you," said Peter. "Shouldn't I wait until Christmas, or until the Larosa girls have their party?"

"The Whites can't be here," said old Mrs Laughley. "They're visiting their daughter in Pennsylvania. And Mr Rocker is helping with the turkey dinner for the Veterans Center. And the Robertos and their children are going on vacation with the Smiths and their children. But this present is from all of us. So, we all want to see you open it. Go on, Peter."

Peter looked down into his hands at the small square package. He felt something moving through him from where he held it, something invisible and permeable and holy, and for a moment he was almost afraid to undo the wrapping paper for fear of it. But at last he opened the box.

It was a basketball card, a Walt Frazier rookie card from Topps, the very basketball card that Elflet had mentioned the night before. The card was in mint condition. It was in a small clear case to protect it. And even though it was only worth about twenty dollars (Peter knew because he had kept track while selling off his card collection over the years) he also knew instinctively that it was perhaps the most perfectly valuable thing he had ever held in his hands. He looked out and saw his neighbors, saw them as the good brave people in his stories who were pressed up against hard times but certainly going to win, and his tongue felt heavy in his mouth.

"Merry Christmas!" they said again.

They hugged him and wished him good night and filed out, fortunately not asking him to say anything because he couldn't. He felt too much. But Little Jim hung back last of all, slipping up close to Peter to whisper with him.

"Don't worry, Peter," he said. "I'll get us the money. How much do we need?"

Peter finally found his voice again.

"Let's say a billion dollars," Peter cleared his throat, "just to be sure."

Peter winked, and Little Jim's eyes went wide. Then Little Jim burst out laughing, and he went jogging out of the doorway to catch up to his grandmother. And Peter was left there, standing by the threshold, holding the card in his hands, turning it over and over, for he could feel it strangely in his heart like an inrush of something that was not quite strength, not quite faith, but more like someone had reached out to him in a dark place so he knew he was not alone. He stared at the card and ran his fingers over it. He looked up, and the young lady with the candy-striped socks - Elflet the elf-let - was still there. And, just as earlier, Peter felt caught and embarrassed that she had seen him in such a private moment.

"That was really nice," he said. "And how interesting is that - the way everyone says you remind them of someone they know. Makes you kind of famous in your way, right?"

"Maybe," she shrugged. "But I'm an elf-let. I always remind people of someone who loves them."

"Really?"

Peter had finally picked up the cold glass of water she had brought him - but Elflet's eyes sharpened and she stepped close to him. She stood in front of him with a directness to her gaze that made Peter put down the glass again. He was suddenly dizzy.

"Don't I remind you of someone, Peter?" she asked.

Peter felt himself suddenly reeling and drowsy on his feet.

"Not your best Christmas, Peter," she told him. "Your worst."

Peter dropped down onto the chair.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

Peter's worst Christmas, or at least his worst Christmas so far, began December 16th when he was sixteen years old. A local retailer had offered him $200 to hold his basketball beside an outdoor-hoop with a water-filled stand. A photographer would take a picture. Then it would become an advertisement for the outdoor-hoop, which the retailer was putting on sale for $99 for Christmas. But Peter's grandmother said no.

"You're only sixteen," she had told him. "And what do I know how they'll use your picture?"

"It's just one picture in a printed Christmas brochure. And it's $200, Granny!"

But at last she met the man in the suit and signed the papers for Peter to have his picture taken and to get $200, which was more money than Peter had ever seen in cash. And he got the money the night before Christmas Eve. He treated himself to the 24-hour arcade and a late-night burger-shop. But while he was eating his cheeseburger at midnight, there came a bang from the door and cold air rushed in. And four young men appeared with masks on.

They walked swiftly through the adjoining convenience-store - which was the only way out - and they crossed into the burger-shop, where there were only two girls about Peter's age at another table. The workers fidgeted nervously behind the counter while the young men looked quickly around and then went up together to the register. Their masks were like big white shapeless faces with black eyes. The biggest young man reached into his pocket. Then, they all threw off their masks and burst into a loud raucous laugh. It was a laugh that had nothing to do with humor or pleasure, but it was rather a kind of animal bravado, a cry, an utterance that meant they were willing to use threat to prove they existed, they mattered, they were important, because deep down they were not sure if any of those things were true.

"Lemme get four sodas," said the biggest young man, who had taken out his wallet.

The others turned and went to the booths by the two girls. They slid in behind the girls, in front of them, and beside them, not even sitting together, but all just staring at the girls, coldly, hungrily, without even speaking. And the girls, who were just younger than Peter, leaned close to each other and pulled up their shoulders to their necks. They whispered together, locking eyes on each other, like that would somehow wall them off so they could be protected and alone again.

"What are you girls up to tonight?" said one of the young men who looked the oldest. "Come on out with us somewhere."

"Actually, we're just going to meet my parents at the train station," said one of the girls.

She was now sliding out from the booth, motioning to her friend, but the young man behind her - who had flat vacuous eyes like he was slightly deranged - put his hand on her shoulder. He pushed her roughly back into the booth.

"Hey now," he said. "Hold up. Wait with us. Hang with us."

"Dammit, Jitter," said the oldest of the young men.

"What? What'd I do? I just want to talk with them the same as you. Look here, girls. Look what I got for Christmas."

There came a snap from down low at the end of the booth, down out of eye level - what the boy held could only be seen by the girls and the young men and Peter, who was watching in the window's reflection. It was a switch-blade, which the boy folded up again and put in his pocket. The girls sat up straight and their eyes went wide. There were no cell-phones back then. The people at the counter were pretending not to notice. And the oldest of the young men - who was about twenty-five, Peter realized - changed booths and slid in with one of the girls, taking her by the wrist so that she winced. This young man had a great long scar down one side of his neck that bulged and twisted on itself under his ear.

"Look, girls," he said. "We're just trying to have a nice early Christmas. You come have a nice early Christmas with us, and everything will be good. Everybody has fun. Everybody gets to go home. Come on, now - "

"Excuse me," said Peter. "You know when this place closes?"

Peter was standing in front of them now, where he had come around from his booth. He had done it without thinking, without a plan, but with a tremble in his whole body, and with a random idea now coming to his mind. The oldest of the young men laughed at Peter.

"What, kid?" he said. "You're interrupting us."

"I want some boilermakers," Peter lowered his voice. "But I don't know anybody around here."

"What's a boiler - "

"Dammit, Jitter," the oldest young man told the one who had the switch-blade. "It's a drink. Now look, kid, we don't have time - "

Peter pulled out his money - his $200 - and the oldest young man looked up. He leaned away from the girl he was holding, and she slid her wrist quietly out of his grip.

"I'll give you $50 and you keep the change," said Peter. "All I need is cups and whiskey and beer. And if you want to drink with me, there's a basketball court around the corner where nobody will bother us. I hate drinking alone. What about it, girls? Can your men drink?"

"We just met them," one of the girls said.

Peter shrugged.

"Anyways," said Peter. "Let's go."

He turned, and his stomach dropped into his knees. He walked on watery legs, because he was sure he had made a fool of himself and had done nothing to help, but when he reached the convenience-store adjoining the burger-shop the oldest of the young men was beside him. They were all with him, in fact. And the girls were in the middle, pushed along from behind by the young man that the oldest had called Jitter. Peter glanced at the girls, trying to get their attention, but already they were all in a group at the counter in the convenience-store.

"Here," Peter told the oldest young man. "You know what we need."

Peter handed him a $50 bill. Then Peter led the others outside to wait, walking beside the crumbly brick facade of the burger-shop with its torn local music posters, while the cars rushed by like slippery deadly animals on the snowy street. Peter took the others across to the basketball court. But when he turned around, he stopped outside the rusty chain-link fence. He looked at the girls and spat on the sidewalk. He pushed one of the girls backwards.

"Why are you still here?" Peter asked them.

"What?"

"I'm not going to ruin my night," Peter handed a $20 bill to the young man called Jitter, "with some twelve-year-old girl getting alcohol-poisoning. Put them in a cab and get rid of them."

Peter kicked the snow and went through the opening in the fence to the basketball court.

"What if we don't want the girls to go?" said one of the young men behind him.

"Then you're all idiots," said Peter coolly, "and I don't drink with idiots. You can all leave."

He walked away from them, over towards the aluminum bleachers at the other side of the court, which were covered in snow, so that he had to scrape them off with some folded cardboard boxes that were beside the trash-can. Peter put the folded cardboard on the bleachers to sit on. And his stomach turned with the terror and fakery of this - of himself who was not himself, who was going to be discovered, and who was probably going to be jumped and robbed at any second. He watched. The young men were mumbling to each other beyond the fence, until Peter pulled out his money and counted it where they could see it.

Then, a moment later, the oldest of the young men had arrived, standing with the others at the fence, where he burst into laughter - like the sound of a dangerous dog, which may at any moment bite. He grabbed something out of Jitter's hand. He gave it to the girls and waved them away, and then he came into the basketball court, leading the others - only the young men now - and he was holding a paper bag in either hand.

"These idiots don't know how to enjoy themselves!" he shouted at Peter and jerked his head at the young men behind him. "Now, let's drink!"

And two hours later, Peter fell through the front door of his grandmother's apartment, with his head ringing like a hammered bowl and not a dollar in his pocket - and his grandmother was awake. She sat at the table. And the look in her fiery old eyes pierced him, even through his drunken stupor, so that he began to weep as he sat down beside her. And now it all seemed so stupid, too. He wasn't a hero. He had done no good. Nothing was ever going to happen to those girls anyways, and he was an idiot who had only empty pockets and a throbbing head and some vomit outside on the sidewalk to show for doing nothing. His grandmother looked at him and got up and went to bed. They never spoke about it, but Peter's Christmas present that year had been a wallet, with a small receipt in it for the bank account his grandmother had opened in his name. Only now there was nothing left of the $200 to put in the account.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

Peter twitched and awakened on his armchair, with Shabby on his feet. His alarm clock was ringing in his small bedroom. Peter limped his way back to reality, out of his strange dream, turning off the alarm in the bedroom and turning on the coffee pot in the kitchen. It was still cold and dark when he took Shabby outside to get the newspaper. He looked out at the gray morning, where a drizzle of ugly hard sleet was falling. The sleet melted and froze like a glaze on the cracked buildings. It hardened on the trash and the cigarette-butts in the street. It seemed to be sealing everything in place, suffocating it.

"Oh, God!" said Peter.

He turned and ran back to his apartment. He burst through the door and fell on his knees in front of the trash-bin, where he had thrown away the contract Mr Stacks had offered. Shabby caught up behind him, growling quietly, pushing on Peter's leg with his head, but Peter only grabbed at the papers. Peter uncrumpled one. It was the electricity bill. He turned the trash-bin over and spread the papers out around himself, like someone crouched to a dirty pool pushing his hands through the top-layer of scum.

"Where is it?" asked Peter. "Where is it?"

And then the first golden light of the day's new sun came through his window. It stopped him. Peter put his face in his hands and shook. He wept while Shabby nuzzled him at the shoulder.

"She took it," Peter mumbled to himself. "She took it, and now she'll know, when I ask. I'm sorry, Shab. I'm sorry."

He stood up and wiped his face, and after he had cleaned the trash and taken a shower, he sat down in front of the unfolded newspaper on his table. He stared blankly at it while eating a breakfast that he could not taste. His hands were trembling. He felt weak and old at the center of himself, hollowed and split like a tree that has been struck by lightning, waiting now only for a good wind to help it fall. Peter's feet were cold. And he looked across the room to Shabby, but Shabby remained by the waste-bin, where he sat, with a fire in his good friendly eyes.

"I'm sorry, Shabbwise," said Peter. "I'm not as strong as you."

Shabby looked away, and Peter sighed. There were no jobs in the newspaper. But there was a sink that was seeping water out of its u-bend on the second floor that Peter would have to fix today. And there was an elevator inspection scheduled for 10am. There was an HVAC flow problem, which might be a busted pump. Except now Peter was just worrying out of habit, he realized, because it didn't matter - he was going to sign the contract and sell the building to Mr Stacks.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

At 11am, after the elevator inspector had suggested a maintenance that would cost about $5000, Peter took Shabby with him to the second floor. They knocked on the door of the young woman, Elflet the elf-let. And her hair was like a wheat-field again when she let them in, and the room smelled once more of the friendly good fire, like gingerbread, that made Peter want to sit down and just be quiet and believe the world was a nice place. Even Little Jim Laughley was there again, sitting on the bean-bag chair, eating pancakes.

"Don't you have school?" asked Peter.

"It's Christmas vacation," said Little Jim. "And Elflet said she doesn't like to be alone."

Elflet set a cup of coffee beside Peter on a small end-table, which smelled of freshly planed wood. The table looked as if it had been cleaned and expertly glued together by hand.

"We're almost never alone," said Elflet, "up with Santa. I'm not used to it. I wish I had a Shabby!"

She laughed and dropped down on the floor, where Shabby yipped while he snuggled up close to her. Shabby burrowed his head into her petting hands until he had twisted himself around with his belly up in the air, with his four legs jittering, while Elflet scratched him.

"Elflet told me your whole conversation with Mr Stacks," said Little Jim to Peter. "I only heard the end of it. And I was hiding, so I didn't see that big gorilla sucker-punch you, but if I had I'd have - "

"He didn't sucker-punch me," Peter shook his head. "He knocked me to the floor, and I deserved it, for losing my temper. I'm better than that."

"You're too hard on yourself," said Elflet.

She was cross-legged on the carpet, humming a Christmas carol over Shabby, petting him, but now she let go and stood up. And Shabby sighed, watching, while Elflet stepped backwards to the corner where the old carpet was goldened with the morning sunlight from the window. Elflet raised her arms. She put one foot in front of the other.

"I can do a handstand," she said. "I learned today, this morning. Do you want to see?"

"No!" Peter got suddenly to his feet. "I mean - sorry. I - actually - I'm kind of - well - actually, do you remember the paper Mr Stacks brought yesterday? Do you know what happened to it? I need it - for - to show my lawyer."

"Oh, I took it! I'm sorry! I didn't realize. I'm always too curious like that, and anyways I couldn't understand it anyways. It's gibberish! Cards should be easy to read, with big soft letters like Love you! or You're the best! Here, I'll bring it to you. Also, don't you want some pancakes? There's more ready now."

She had gone right past him in her nimble way, as if the weight of her never really needed to come down anywhere, on any foot, except for the pleasure of feeling herself bounce perhaps. And now she was around from behind the counter again, with the contract in her hands. She smoothed it out. It looked cleaner, and it even smelled better when she handed it to Peter. He flipped to the last page. The date was right, and the amount was still the same - it had been no trick of his eyes, no hopeless half-dream, but it was really five times as much as the original offer. It was enough for Peter never to have to worry about money again, never to have to wake in the night feeling sick with rashes on his skin from scratching in his sleep, never to have to tighten his stomach in the morning and force himself through the motions of the day instead of just sitting down with his head in his hands.

He looked up again, and Elflet and Little Jim were staring at him. And there was a gray plainness suddenly to their faces, even in spite of Elflet's beauty and Little Jim's perpetually open cheerful smile. And the sunlight in the windows, too, was shifted, graying from the gold that had been there a moment ago. Now, it was the monochrome that Peter was used to seeing in his own small apartment, as if the sun had to cover its eyes to look at him. In fact, it seemed now to Peter that the whole world was suddenly covering its eyes ashamedly while it looked at him, and all of time, too, and all of everyone of all time, too, and most especially his grandmother, who was there in the gray sunshine at the window looking at him with her mouth open in disbelief. Peter slumped.

"What?" he asked. "No - no, thank you. I don't need any pancakes."

He straightened out his clothes.

"Anyways," he said. "Thanks for - for the - and anyways, back to work, I guess! You guys have fun!"

Peter gave them a big weak smile and whistled dully for Shabby. But Shabby moaned and lowered his head and would not look. And - at that moment - Elflet sprang at Peter, like something suddenly in technicolor from a monochrome world, leaping into reality, so vivid and emotional and heedless was the way she grabbed onto him. She held his wrist. And her touch made all the colors of the world return around Peter, and there was golden sunlight once more, and Peter's grandmother in the window was no longer appalled at him.

"Promise you won't sign it yet!" shouted Elflet. "Please! Please promise to wait for my Christmas miracle!"

She had him by the arm, tugging on him like a child that's too weak to pull itself up but too strong to let go.

"What?" asked Peter. "What? No, it's for my lawyer! I'm just going to show it to my lawyer."

"Then swear!" she cried at him. "Swear! Swear! Promise you'll wait until after Christmas! Please, Peter! Promise you'll wait!"

"Okay, I promise! I promise! It doesn't matter, anyways, because it's only for my lawyer. It's only just for my - it's for - it's for my lawyer, okay! Fine! I promise!"

He backed up and got outside and closed the door. Then he turned and ran downstairs to his apartment, without even waiting for Shabby, because he was crying.

This story is in the paperback

How To Look Like You're Reading A Book

on Amazon for $12.99

or you can keep reading free.

It was sad, and a waste of friendship that Peter regretted all his life afterward, because for the rest of the week he avoided the young lady - Elflet the elf-let - for the shame he felt in her presence. She would step out of her door and smile at him when he was in the hallway. But he would only put his head down. And he would hear her singing when he opened his window in the morning. He would listen, smiling, until he realized what he was doing, and then he would close the window again and retreat into the empty anger of himself. He seemed to be carrying the gray light of December around with him like a weight on his shoulders. And then suddenly it was Christmas Eve, like that, without a warning, and Elflet was knocking on Peter's door.

"Peter?" she called to him. "Shabby? The Larosa girls have started their party on the roof. It's so nice! Let's go up together!"

Peter stood there, between his desk and the door, shaking, trembling as if he were a child, until Shabby pushed him at the leg. Shabby made him take a step forward, and Peter forced a smile.

"Hello," Peter said, opening the door. "You look happy, Elflet."

"Oh, Peter! You're still worried! I can see it! Come on, now. It's Christmas. It's the one time when you get to just be happy and you don't have to have a reason. Come on, Peter! Let's go up to the party together!"

She had danced into the room. She was wearing jeans and a red-and-white striped Christmas sweater that matched her socks. The sweater had heart-shaped patches at her elbows. She took one of Peter's hands, spinning herself underneath it, so that she was now at his side and pressed next to him with her arm in the crook of his elbow. And then she tipped forward, and with her free arm she scratched Shabby. She scratched him around the ears and neck and down his back, so that Shabby stood there stretching, howling softly, while Elflet hummed her Christmas carols. Then Peter's old grandfather clock chimed 9pm, and Elflet straightened up suddenly.

"Oh, I forgot!" she said. "Your present's still in my room! But wouldn't it be fun to open it on the roof with everyone else? Did you get me anything, Peter?"

She looked up at him.

"Of course," he lied. "But I've been too busy to wrap it, I'm sorry. Why don't you go on up with Shabby, and I'll be there in a few minutes."

"Okay!"

She turned and marched out happily, leading Shabby along. But Shabby, of course, glanced back at the threshold and barked warningly at Peter. Then they were both gone, and Peter was alone. And, somehow, the idea of buying a present for Elflet made Peter happy for the first time all week - this strange young woman, with her Christmas carols and her socks and her enormous affection for Shabby, needed a Christmas present. It was the smallest worry imaginable. Peter grabbed his jacket and dashed outside into the cold New York City December.

The shops were closed. But Peter only laughed at each window he passed - he felt a kind of madness, a kind of release, because at last he had a reason to feel what he had been feeling all week, which was debilitating confusion. He was bound to go wrong. What exactly could a man buy for a young woman who thought she was an elf? She made her own sweaters, apparently. And she made her own end-tables. And Santa made her shoes. So, Peter would certainly choose something wrong for her (just as he was certain that, no matter what, he would make the wrong decision about his building) and finally he just closed his eyes and spun around once with his arm out. When he finished, he was pointing at the only open shop, a convenience-store. He walked in and chose a pair of sunglasses off a rack and a Christmas card.

Peter felt in his pocket for a pen, and he wrote for Elflet a card that said Love you! You're the best! and he grabbed peanut-butter for Shabby, too. But, when Peter was putting the pen back inside his jacket, he touched the envelope in his inner pocket. It was the contract that Mr Stacks had given him. Peter had already signed it. Now it was folded up and sealed in the envelope, and, almost as if by fate, Peter was looking out through the window of the convenience-shop - just across the street, in front of the post-office, stood a big blue mailbox. Peter paid and went out and crossed the road.

Peter just stood there in front of the mailbox. He stood there for a long time, just thinking, just feeling the cold on the back of his neck, and the way that the air crept around him with the night, and the way that New York City held itself up so nobly and determinedly and even defiantly in spite of the harsh awe-inspiring winter. And Peter missed his grandmother. He reached into his pocket and removed the envelope with the signed contract. He put it in the post box, and he told himself it was over, it was done, and now he could finally stop weighing it in his mind and say good-bye. He took off running towards his building.

But now Peter heard it - the madness in his own laughter, and instead of letting go, he had only lost himself, broken himself. He was not in his story anymore. He was not one of the good brave people who were pressed up against hard times but holding on to the end, because he had given up. It was over. Peter couldn't breathe. He fell over hyper-ventilating when he reached his building, and he vomited in the street and staggered to the door.

"Peter!" Elflet leaned over from the roof and called to him. "Peter! Come up! We're having so much fun, and I gave Shabby a sweater and he loves it!"

Peter staggered into the hallway, then into the rickety elevator. He blinked, and he was suddenly on the roof.

"Peter!" shouted Elflet. "What's wrong? Here! Oh, Peter! Sit down! Sit down!"

Peter fell onto a sofa that had been hauled up on the roof. The sofa was closed up in a tall outdoor marquee, where there was also a big tall propane space heater and even a television in the corner with an extension cord. But for Peter life was on mute, soundless. In front of him, there was a great group of people on the roof. They were holding plastic cups and paper plates. And they had never even noticed Peter stagger in quietly, or maybe they had only pretended not to notice him, because they thought it was the best way to help - just give him a moment. Or maybe they were ashamed of him. Peter sat there and blinked. He was in a stupor. It wasn't until almost midnight that he finally came to himself, sitting up, because Elflet was by him on the sofa where she was shaking him.

"What's wrong, Peter?" she asked. "What happened?"

He could only make a small movement like shrugging.

"Peter, I want to help you!" she said. "Here, it's midnight. It's Christmas! Open your present, and you'll feel better. It's time for my miracle. I hope it's a really happy one!"

She set the box in Peter's lap, and he only looked at it. And then Elflet lifted his hands and put them on the wrapping paper. She started him mechanically, almost like an old prop-plane or a hand-pump or a crank-motor, with Elflet moving his hands for him, until Peter could go through the rote motions on his own. His fingers unwrapped the paper while his brain and emotions sat unmoved within him. At last the box was opened. Peter was leaning forward over it. He reached in and pulled out the detritus of New York City, the old cardboard and newspapers and lottery tickets and styrofoam and candy wrappers.

"It's just trash," he said.

"And what else?" asked Elflet.

"There's nothing else."

Elflet lunged forward and grabbed the box and picked it up and stared into it.

"What else did you put in there?" Peter asked.

"I didn't put anything else in there!" she said. "It's supposed to be a Christmas miracle! I can't put it in there myself! That was just padding, in case it rolled around. I thought it was going to be a basketball, like from when you were little and you played with Mr Rocker. And I got the biggest box I could find! What happened?"

She dropped the box and looked around, as if something might be whizzing secretly past her through the shadows, or in the air, or somewhere, anywhere. She stood up like she had to be ready to pounce when she found it, and there was a wildness in her eyes that was not entirely for Peter's sake, yet it was no less holy in its selfishness. She jerked and jumped when old Mrs Laughley came over. Old Mrs Laughley grabbed Elflet's elbow, and Peter sank back into the sofa again. And he sat there, listening, but not listening, while Mrs Laughley jabbed her hand through the air. She had her other arm around her purse, and she had on her outdoor hat and coat like she was going somewhere.

"And thank you very much for your help, Peter!" she said with a snap.

"What?" he said.

"Don't WHAT me!" she said. "Your grandmother would be ashamed of you! I've asked you five times about Little Jim now and - forget you, I'll find him myself!"

"Little Jim?" he asked.

"She hasn't seen him since lunch," said Elflet. "He hasn't come home yet."

"What!" Peter jumped to his feet. "We have to find him! Let's go! Get your phone! Wait!"